2017 Exam Program

FACEM Exam Resuscitation

Summary

(1) Briefly Review suggested articles and blog post

(2) Complete the selection SAQ questions to an allocated time (download below)

(3) Local candidates meet or email questions to andrewRcoggins@gmail.com for feedback

Download for the PDF of Resuscitation Questions:

Cardiac and Resus SAQ Version 1

Cardiac and Resus SAQ Version 2

Background Reading

Reading for the FACEM Fellowship Exam on Resuscitation:

- Overview

- 2010 – Major Changes

- ARC Website

- COSTR (2010) – see timetable below for 2015 guidelines

- ILCOR Website

- Topical Links

- New Therapeutic Hypothermia Paper (2013)

- “Targeted Temperature Management” (2013)

- Post Arrest Care Overview (2011)

- New Therapeutic Hypothermia Paper (2013)

- Resuscitation PDF List

- Old Therapeutic Hypothermia ACEM Guideline – Resus – Hypothermia

- Post Cardiac Arrest Care – Resus – Post Resus Care

- Resus Resus – Equipment

- Medications – Resus – MEDS

- ALS Introduction – Resus – ALS intro

- BLS Summary – Resus – BLS summary

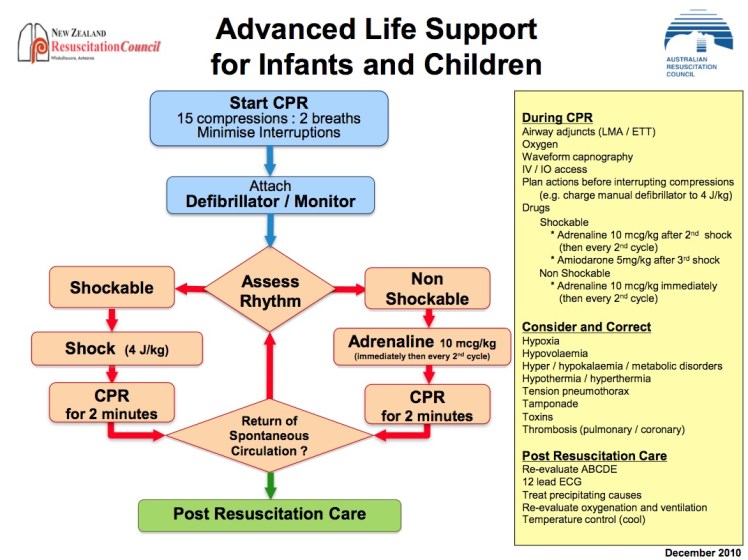

- Paediatric CPR Guideline – Resus – Paeds Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

- Intra-arrest Thrombolysis EBM Review – Thrombolysis during Resuscitation

What about the 2016 Guidelines?

- Currently under construction and investigation.

- The timetable for the upcoming development of the 2015 recommendation is as follows:

Resuscitation

A Review for FACEM Examination

General Points

- In the exam there are always questions on Resuscitation – For example in the 2012:2 paper the examiners asked for a ‘overview of the 2010 changes’. Resusciation is often covered in the SAQ and SCE sections

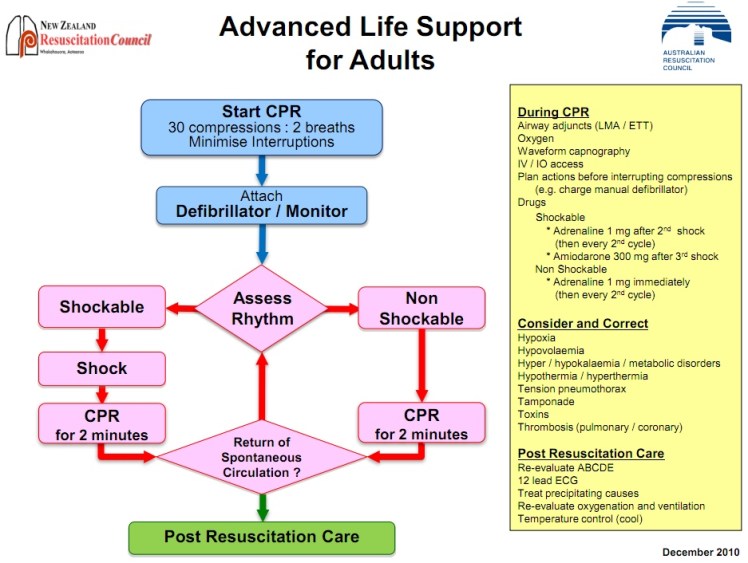

- Latest Australia and New Zealand Guidelines

Defibrillation

- Effectiveness is dependent on Trans-thoracic Impedance.

- To minimise impedance use 10-13cm pads, 5kg pressure

- Defibrillation should theoretically occur in Expiration

- Use Paste with older defibrillation ‘paddles’ (unusual in Australia)

CPR

- Competing ‘Cardiac’ Pump and ‘Thoracic’ Pump Theories to explain efficacy of CPR

- Recent trend toward minimsing interruptions in CPR compressions.

- An effective ‘pressure head’ takes time to build up with Chest Compressions. Therefore, effective CPR depends on minimising delays and interruptions

- At most, good CPR provides 20% of normal cardiac output

Cardiac Arrest

- Recent NSW study showed reduction in Australian survival rates between 2004 and 2009 – may be due to a reduction in rates of VF/VT – a concerning trend

- Worldwide – Out of Hospital 0-21% survival, 8% overall

- Extensive data collection in cardiac arrest prospective registries such as PAROS (Pan Asian Registry)

- In hospital mortality 13.8% (Cameron)

- Outcome is better in witnessed arrest, early CPR, VT, VF

- Outcome also better with reduced time to defibrillation

- Larsen et al (1993) – 5.5% reduced survival per minute (composite data)

- Survival is quoted as up to 67% if BLS/ALS measures are provided early (Cameron)

- ‘When to stop’ – controversial (generally >20mins of asystole and low ETCO2) – prognostic factors are an evolving area of study (may change in 2015 guideline)

Evidence Based and Consensus Guidelines

- ‘COSTR’ – Consensus on Scientific Treatment Recommendations – see above for 2015 guideline timetable

- Uniform Reporting (Utstein Method) has improved accuracy of data

Educating the Public

- In terms of Public Health Hands only CPR may be more effective in terms of teaching and education.

- The SOS Kanto (2007) and Arizona Studies demonstrated improved survival in the Chest Compressions only patients compared to the ‘ABC’ patients

AED

- With AED – Ontario study (Stiell et al) demonstrated a survival benefit in public places.

- AEDs in the home have not been shown to improve outcome

2010 Guideline Changes

Paediatrics

- Intraosseus Lines are emphasised:

- Indications – Unable to obtain IV access in an emergency/cardiac arrest.

- Complications of IO – Bone (Growth Plate) Injury, Cellulitis, Fracture, Compartment Syndrome, Extravasation of Drugs, Osteomyelitis.

- Contraindications of IO – Fracture, Infection

Post Cardiac Arrest Care

- This is a topical area:

- Recent Changes and Key Papers in 2002 showing benefit of Therapeutic Hypothermia

- Key article – Stub et al Circulation 2011

- This article and other similar commentary on the subject suggests cooling the patient as well as optimum fluid, BP and supportive care management:

- Fluids – are generally thought to be a good thing post cardiac arrest o BP – aim for relatively High BP – MAP >75

- Avoid Hyperoxia

- Avoid Hyperventilation

- Arrange Catheter Lab – ASAP

- Consider IABP and AICD

- Check ECG – for QT, Brugada, T wave changes

- Good Supportive Care

- Early ICU Referral

- Document Neurological Signs Prior to Intubation and Ventilation

- BSL – monitoring and control

- Angiography is warranted in many post cardiac arrest patients even without classic features of a STEMI on the ECG (prospective observational data)

- Aggressive cooling strategies adopted since 2002 are now balanced against a 2013 paper showing no difference between 33 degrees and 36 degrees cooling

- Cooling = Therapeutic Hypothermia – but consider limited “targeted temperature management” strategy

Passive and Active measures should be considered when cooling the patient:

- 3 deg saline given IV

- ICE to groins and axilla

- End Points of cooling – aim for 32-33 degrees

- Post Drowning care is also topical for the FACEM exam

Hypothermia Arrest

- Follow specific protocols on rewarming

- Limited use of drugs and defibrillation

- Prognosis varies – survival after long periods of “down time”

- For more details see out FACEM notes – FACEM Notes.pdf

ECMO

- Trial currently on-going in Melbourne, Australia

- Dedicated discussion – Click Here

Thank you for a great summary. I may be reading it wrongly, but do you really mean 8% mortality? or 8% survival? Also, for those of us in smaller hospitals, any comments on intra-arrest lysis?

We recently had discussions after a local case of successful intra-arrest thrombolysis:

Click to access thrombolysis-during-resuscitation.pdf

Historically patients have done worse with Cardiogenic Shock and AMI with thrombolysis – but in the next stage (arrest) there has been mixed observational data. There is both prospective and retrospective data available with varied results. The American Heart Association and Australian Resuscitation Council have been candid in their 2010 recommendations on this issue.

The American Heart Association 2010 ALS guidelines state:

– Fibrinolytic therapy was proposed for use during cardiac arrest to treat both coronary thrombosis (acute coronary syndrome) with presumably complete occlusion of a proximal coronary artery and major life-threatening pulmonary embolism.

– Ongoing CPR is not an absolute contraindication to fibrinolysis.

– Initial studies were promising and suggested benefit from fibrinolytic therapy in the treatment of victims of cardiopulmonary arrest unresponsive to standard therapy. But 2 large clinical trials failed to show any improvement in outcome with fibrinolytic therapy during CPR. One of these showed an increased risk of intracranial bleeding associated with the routine use of fibrinolytics during cardiac arrest.

– Fibrinolytic therapy should not be routinely used in cardiac arrest (Class III, LOE B).

– When pulmonary embolism is presumed or known to be the cause of cardiac arrest, empirical fibrinolytic therapy can be considered (Class IIa, LOE B).”

Anecdotally at least we have had success in our hospital. Combining this experience with the message portrayed by the ARC and AHA makes it hard to take a definitive take home message…

My view is in patients which suspected PE or patients who have witnessed arrest or bystander CPR and favourable ‘numbers’ in the ED (and/or where there is no ECMO access) then thrombolysis seems like a reasonable therapy to consider being aware of the caveats and paucity of evidence.

Andrew

Will be interesting to see what the 2015 guidelines say – Resus seems to always come up in the FACEM exam